Renewing and recurring

July 10, 2025

The giving rate is falling in the United States. Over time, fewer and fewer people report giving to charity. It is a worrying sign for the nonprofit sector, but there is reason for hope as well.

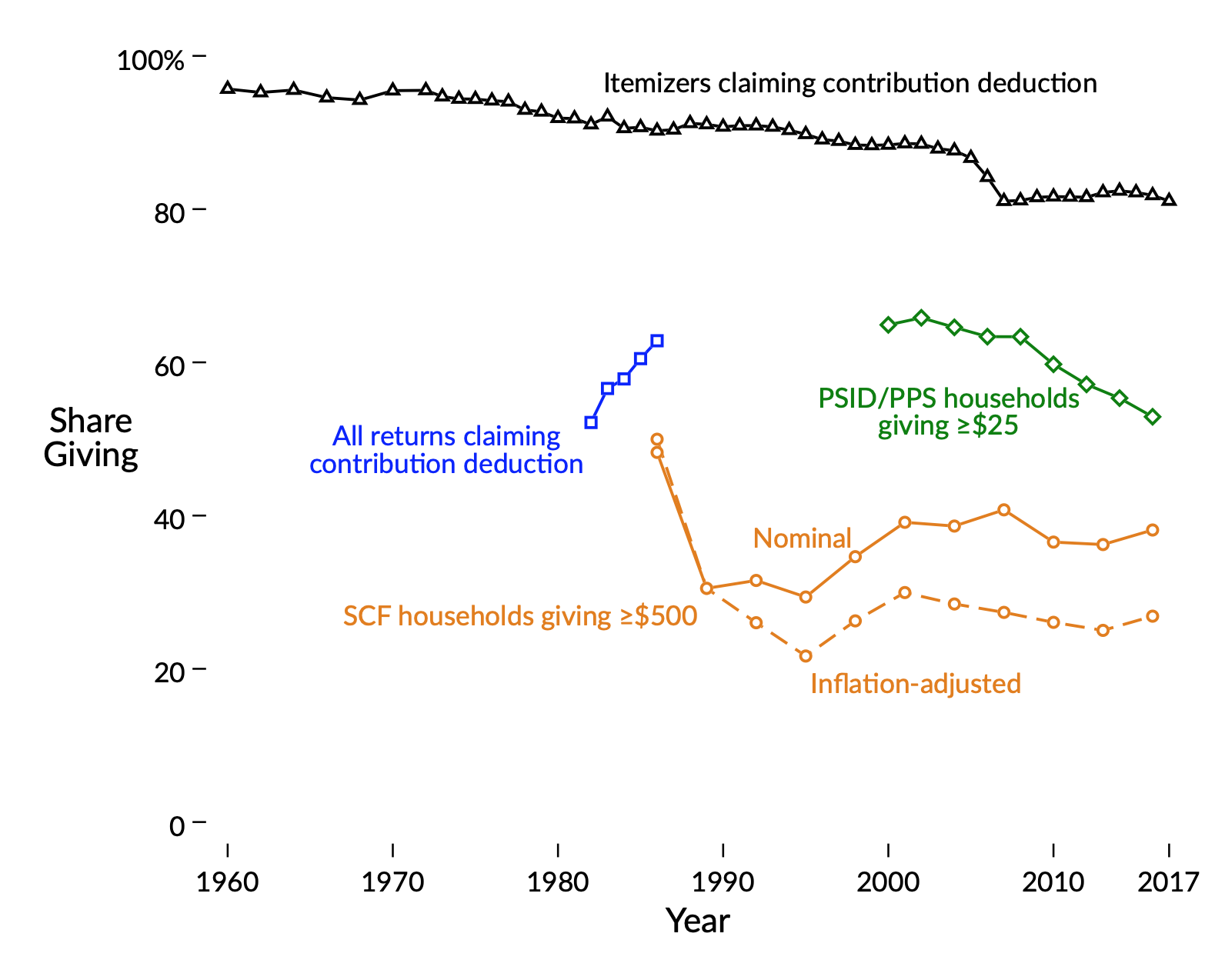

Over time, fewer Americans report making charitable contributions, and the rate of change is dramatic. In the Panel Study of Income Dynamics survey, for example, the same households have been asked whether they give to charity every other year from 2000 to 2022; in the 2000 wave, For the most part, charities have been able to tread water by increasing the donations they get from their largest donors, which has kept their overall fundraising approximately level even as the number of donors has shrunk.

Vertical axis marks the share reporting strictly positive charitable giving; horizontal axis marks the year. Triangles plot the share of itemizing tax returns taking a charitable contribution deduction. Squares mark the share of all tax returns claiming a deduction for charitable giving over the period 1982–1986. Diamonds plot the share of households in the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics survey reporting at least $25 in charitable giving. Circles mark the share of surveyed households who report giving at least $500, in nominal terms (solid line) and in real 1989 dollars (dashed line) in the Survey of Consumer Finances. From Duquette, Nicolas J. “The Evolving Distribution of Giving in the United States.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50, no. 5 (2021): 1102–16.

Vertical axis marks the share reporting strictly positive charitable giving; horizontal axis marks the year. Triangles plot the share of itemizing tax returns taking a charitable contribution deduction. Squares mark the share of all tax returns claiming a deduction for charitable giving over the period 1982–1986. Diamonds plot the share of households in the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics survey reporting at least $25 in charitable giving. Circles mark the share of surveyed households who report giving at least $500, in nominal terms (solid line) and in real 1989 dollars (dashed line) in the Survey of Consumer Finances. From Duquette, Nicolas J. “The Evolving Distribution of Giving in the United States.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50, no. 5 (2021): 1102–16.

It’s also concerning because we value the act of giving itself. If charities were just any other type of product, it might not be so concerning that most of the revenue was coming from a shrinking minority of more intensive activity; like, if US automakers’ profit has been maintained by making bigger markups on fewer vehicles, that would be interesting and might suggest that those firms are on a less sustainable business trajectory than topline numbers would suggest, but—no offense to any gearheads reading this—there would be no reason to be concerned about equitable participation in auto spending for its own sake.I have no idea whether this correctly describes the trends in US automakers, though given the increasing share of new vehicles that seem to be pickups made from enough steel and electronics to have made a small tank instead, it feels true.

But giving isn’t buying a car: it is an act of civic selflessness that strengthens communities. Social observers, including most famously sociologist Robert Putnam, have tracked a variety of such civic behaviors in the United States over time, including charitable giving.Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000. These behaviors have tended to trend in the same direction: down. People who give less often are therefore not only not supporting worthwhile charitable organizations, but are indicative of a broader societal decline in civic engagement. Yikes!

There are a lot of theories for the decline of participation in charitable giving. Maybe rising inequality means a lower share of the population with enough disposable income to give. Maybe people are still giving, but through platforms like Gofundme that are not charities. Maybe the missing donors’ preferred organization was their church, and the decline in giving is, in tandem with cratering American religiosity, a decline in tithing.For example, Pew surveys have tracked a fall in Christian share of the US population from over 90% 50 years ago to under two-third today, with further decline expected. Maybe the decline of mass media and postal mail have undermined the effectiveness of traditional mass-fundraising methods without offering a replacement. Perhaps diminished federal income tax incentives for giving have decreased the appeal of a gift.

Maybe fewer people are interested in giving, period.

We don’t know which of these explanations is the most important, and indeed the answer is likely to be some mix of many of these. Scientists and fundraisers alike have their work cut out for them to figure out how to get people to care about giving, to remember to give, and to get them excited to increase their giving.

Fortunately, there is a tool that is increasingly useful for increasing giving in the present moment. Automatic, recurring monthly gifts are a rising share of contributions, and charities are increasingly making use of this tool to make their donations more reliable without having to constantly pester their donors.

Giving automatically is on the rise

The good news is that while giving participation may be falling, increasing comfort with automatic, recurring payments is on the rise, helping donors and charities make repeat giving easy and predictable. If you give to charity, you’ve probably seen examples of this: donation links on web pages will give you the choice to make your contributions monthly instead of one-time-only. For example, here is the donation portal for GiveDirectly:

Pretty easy! You can choose a one-time gift or a monthly gift; the buttons to make the choice are big and obvious.

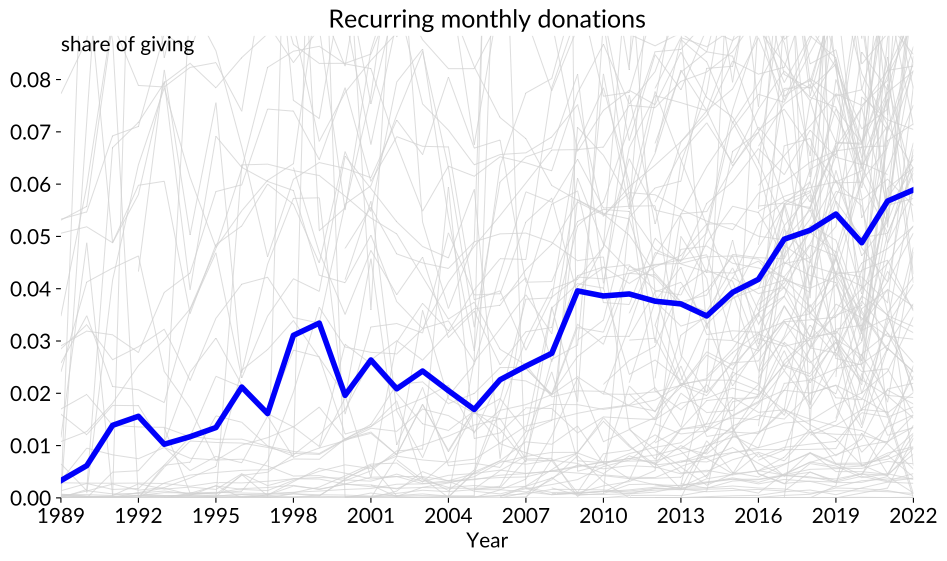

In the days of paper check and postal mail, a recurring contribution wasn’t an easy thing to start or to cancel. Now, it is straightforward, and a rising share of donors choose to give this way. In new work, I calculate the share of donations made by monthly recurring donors to US charities over time, from two different data sources.This work is not posted publicly yet, because much of it is still being written and rewritten; I will edit this post to link to the manuscript when it becomes available For technical reasons, there is not one “right” way to measure the share of recurring donors, but no matter how one slices the statistics, the story is clear: the share of giving coming from recurring gifts is going up.

Here is one plot from my work. You can see that 30 years ago, the median charity in my sample (marked by the thick blue line) did not receive much in the way of recurring gifts. Over time, the share has marched steadily upward; in 2022, when these data end, about six percent of all dollars given came from monthly recurring contributions.

Recurring contributions as a share of total contributions. Each thin grey line plots the recurring share of giving for an individual charity. The thick blue line plots the share for the median charity.

Recurring contributions as a share of total contributions. Each thin grey line plots the recurring share of giving for an individual charity. The thick blue line plots the share for the median charity.

And here is the thing about recurring donations: the people who make recurring gifts donate more money, more consistently, by a large margin. My ongoing research finds that compared to donors who make one-time gifts, recurring donors: (1) give one-third more, on average, than non-recurring donors; (2) give again the following year over 90% of the time, compared to less than half the time for non-recurring donors; (3) are nearly twice as likely as non-recurring donors to increase their giving; and (4) are much more dependable donors to charities, not only in the present, but years into the future

So while these gifts are still a small minority of all giving for most charities, they are some of the highest-quality contributions the charities receive.

What should charities do?

If charities want to grow their donor base, encourage their existing donors to increase their giving, and make their donation revenue more predictable — and I think most donor-drive charities want all of those things — then they should nudge donors toward making their gifts recurring.

To be clear: recurring contributions are not a cure-all, and charities could go too far asking donors to make monthly gifts. Many donors will not be interested in making their gifts a monthly gift. Some may want to make a one-off contribution in honor of a friend or family member and never give again (and will be mildly annoyed by the years of asks that will follow). Some may be resistant to signing up for additional automatic monthly charges at a time when every service, app, and media outlet seems to beg users to subscribe — I am one of these people. Hypothetically, a charity that pushed potential donors toward monthly giving too aggressively might lose the gift entirely.

And more generally, charities can’t assume that donors undergo some sort of magical transformation when they choose to make a recurring gift. Chances are that the choice to make a recurring gift reveals that the donor was already one of the most enthusiastic supporters of the organization to begin with; the association between recurring giving and larger, more dependable gifts is probably some mix of both greater interest in the organization and and effect of recurring contributions’ ease of use on donation amounts. Or—to put it terms academics love—the causal effect of becoming a recurring donor on the amounts people give is ambiguous, and the raw correlations likely include selection into becoming a recurring donor by those who would have given generously anyway.

But the effect is unlikely to be all selection. Making a monthly gift is a convenient, easy way for busy donors to support causes they care about; there’s no need to write a check periodically or think hard about how much to give. An automatic deduction also averts the well-known problem of immediate pain for an abstract benefit; like a payroll deduction for a retirement account, an automatic donation is close to money the individual doesn’t actively choose to give up.Of course, workplace giving campaigns like United Ways pioneered this approach with literal payroll deductions; the decline of these campaigns may also be a reason for falling giving!

Charities are aware of the advantages of recurring gifts, but not all have moved to adopt the strategy. While most donation web pages now have a monthly giving option, it is not a universal option yet. One of the two charities I give to most consistently—a very large and successful, donor-driven organization—does not offer a monthly giving option on its donation page.

Furthermore, while many charities will accept a monthly gift, expressly asking for them is not widespread. The other charity I give to most consistently has a monthly giving option, but I had to look carefully for it as I wrote this blog post to see that it even exists. Instead, that organization relies heavily on more traditional strategies like matching promotions, fundraising events, and challenging donors to match their previous-year gift. If it has ever explicitly asked me to become a monthly donor, I have no memory of it.

But not every organization is like this. I also make a small monthly gift to a third charity I personally support, though not as actively as the other two. There is no reason to make a monthly gift to that charity but not to the others; if I had to choose one of the three charities to stop giving to, it would be the one I make monthly gifts to. The difference is that the third charity asked specifically, for a monthly gift instead of a one-time contribution.

Would I have given less if I had made a one-time gift? Over the short run, probably not. But over the long run, who knows? How long will it take me to make an active decision to stop making my monthly gift, rather than let it roll along, through financial inertia?

And that, I think, is the next frontier in successful fundraising: finding a way to ask donors to give, not with an option to give monthly, but with a sincere and heartfelt request that they choose the monthly option if they can.If you are a fundraiser interested in trying a pitch like this as an experiment and would like an academic collaborator, please reach out. My hunch is that while many donors will not be interested in monthly giving, there is a large number of people out there who would be happy to make their gift monthly. But you have to ask.