Some thoughts on OBBBA

August 7, 2025

While I was off the grid, the Wall Street Journal published some astute analysis of the likely effects of the One Big Beautiful Bill on giving, with some excellent thoughts from a variety of experts. The upshot is that it will be hard to predict the overall effect of the bill on giving. Though the changes to tax incentives for giving are very large, some will act to increase giving, while others will decrease it. The overall effect on charitable giving therefore looks ambiguous. Some unsigned posts on the Nonprofit Law Blog here, here and here note that published estimates of the effects of these different provisions suggest that they will roughly cancel each other out, and that attempts by tax planners to move giving between tax years may obfuscate the size of the response for some time to come.

I’m willing to make a specific prediction: compared to the world where the OBBBA did not become law, Americans will give less to charity. The effect size won’t be ruinous, but especially for charities that depend on philanthropic support, it will matter.

Floors, ceilings, rates

Part of what makes the bill hard to analyze is that the changes to incentives vary a lot. Under classical utility-based decision theory, one ought to care about decisions at the margin of the relevant choice; a tax increase or decrease might make you richer and happier (or the reverse), but unless the changes in tax incentives make you prefer a different choice from your availabile possiblities,Or unless the tax change alters your choice set itself, which is kind of the same thing. then you should stay the course.

With one exception, the OBBA does not do much to tweak the actual rate one pays for charitable giving without limit. If you are an itemizer, then, the new 0.5% floor should not affect your giving unless your giving is between 0 and the floor (in which case, because you get less of a subsidy, you decrease your giving), or possibly just over it (because you lose most of your tax subsidy, you decide to stop giving for the most part).Those who already give 0 are unaffected by this policy change because they can’t give less than they already do. But for donors who give much more than 0.5% of their income, the loss of the floor amount is annoying but unlikely to affect their decision.

For example, itemizers who give 2% of their income to charity will only be able to deduct 1.5% under the new policy. Annoying! But will it change their giving decision? If they reduce their giving by half, to one percent of income, they don’t lose half their deduction; they lose two-thirds of it, because the deductible amount is now 1.5%-1%=0.5% of AGI. And if they choose to increase their giving, then those gifts are fully deductible – the floor is equivalent to a lump-sum tax for anybody who is not close to the 0.5% floor point in their giving.

The same logic applies, though in the other direction, to the increased deduction for nonitemizers. Giving will be deductible for nonitemizing households up to $1,000 ($2,000 for married filing jointly), up from 300/600 in 2025. For any nonitemizer who already gave less than the old ceiling — or substantially more than the new one — this change should not affect their choices. Only those who gave between the two ceilings have an incentive to change their giving.

For these reasons, while I do think these floor and ceiling policies will affect giving, I expect their effects will be muted, at least relative to one other policy change: a limit on the value of itemized deductions, including the deduction for charitable contributions. While the top tax rate for high incomes will continue to be 37%, starting next year, only a rate of 35% will apply to deductions; the remaining 2% in tax will still be paid. For taxpayers in this category, the cost of giving to their favorite charity will rise from 1-0.37 = $0.63 to $0.65, a price increase of over 3%.For simplicity, I’m just talking about the direct federal tax change; actual tax situations get raplidly more complicated once you start grappling with issues like whether the donor pays state income tax, or local income tax, or can deduct their state and local tax from their federal tax, or can deduct charitable giving from that state and local tax, do they pay Medicaid surtax, or NIIT, or can they avoid capital gains by donating appreciated property, et c.

Follow the money

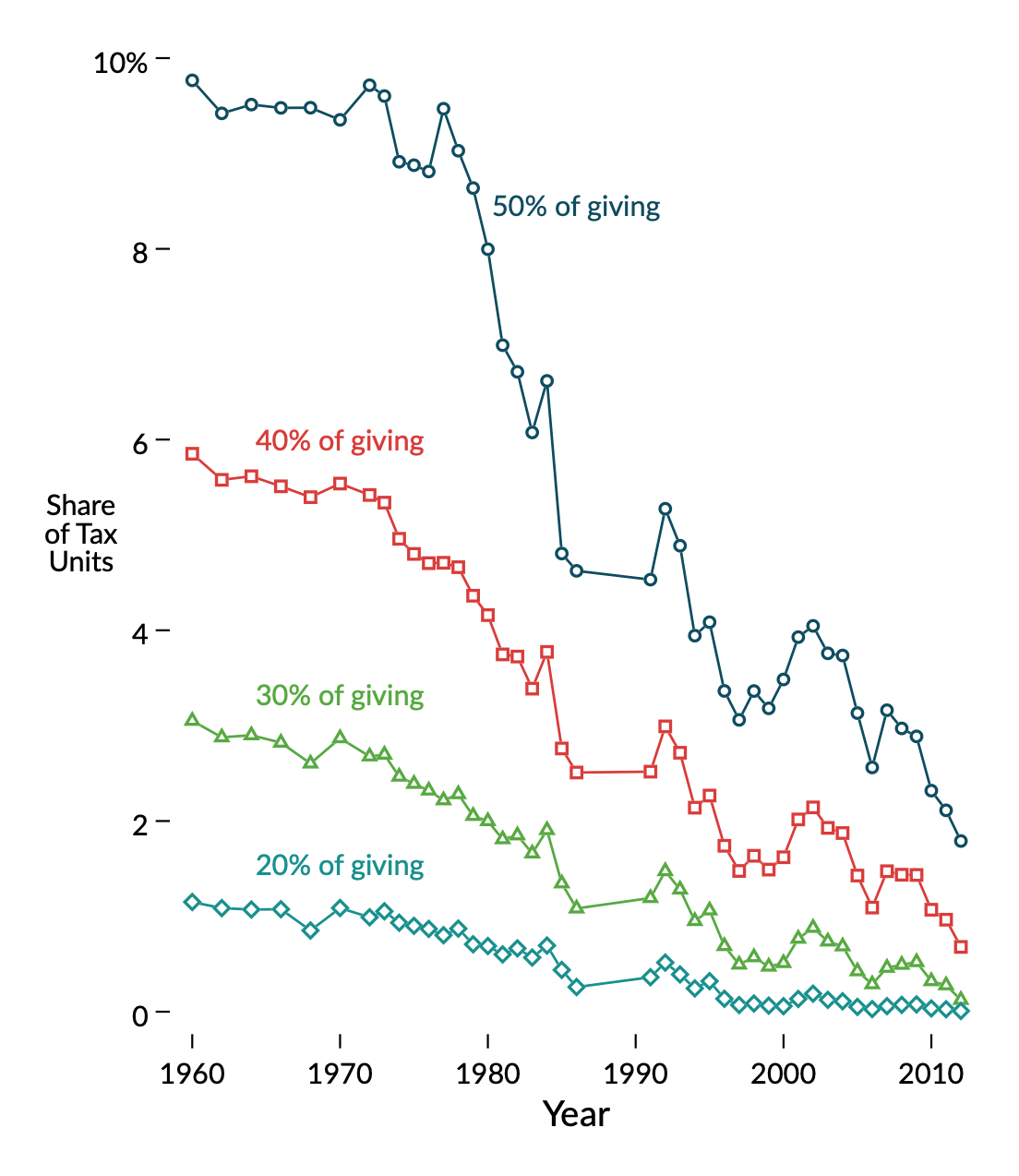

Though the change in deductibility from 37% to 35% looks tiny, I predict that it will dominate the overall response. Not because the change is dramatic, but because the affected giving matters a lot. As of 2012, most of the giving in the USA came from less than 2% of all tax returns; a third of all giving came from a tiny share of one percent of all returns. This was the end point of a multidecade trend, whereby the widely distributed, civic nature of American charitable giving became concentrated in the hands of a few very wealthy and very generous philanthropists.The data stop in 2012 because that was the last year of data available when I wrote and published this study over 2019-2021. While it is now 2025, there is little reason to think the trend hasn’t continued in the past decade.

Plotted series report the share of tax units responsible for fixed shares of total individual giving over time. From Duquette, Nicolas J. “The Evolving Distribution of Giving in the United States.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50, no. 5 (2021): 1102–16.

Plotted series report the share of tax units responsible for fixed shares of total individual giving over time. From Duquette, Nicolas J. “The Evolving Distribution of Giving in the United States.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50, no. 5 (2021): 1102–16.

While giving by small-dollar donors matters, it’s a long tail on a very skewed distribution; much of American giving is accounted for by multimillion-dollar donations. If you are giving $5 million to your favorite charity, you don’t care if the limit on deductibility of state and local tax is $10,000 or $40,000; it’s nearly irrelevant to you.

However, people who give in such large amounts do, typically, have very good tax planning.Another reason that I don’t think the 0.5% floor will matter all that much is that very wealth people are good at keeping their taxable income low in general. The smaller the income, the smaller is 0.5% of that income. They will know that they will likely only be able to deduct 35% of their gift instead of 37%. And they will adapt.

How much will they adapt? A decent rule of thumb is that a 1% increase in the after-tax cost of making a charitable contribution causes roughly a 1% decrease in charitable giving.There are way too many academic papers on this topic to cite just one, and the question is surprisingly contentious; many estimates much greater or smaller than this one-for-one rule have been found. If you want to read just one paper on the effects of tax incentives on giving, I suggest Han, Hungerman and Wilhelm’s paper on the 2017 TJCA. We can use this rule to back out a very rough, back-of-the-envelope guess at the likely effect of this policy change on overall giving.

In 2022 – the most recent year of tax data available as of this writing – tax returns in the 37% rate bracket made with $500,000 more in adjusted gross income itemized about $170 billion in giving.Calculated by adding cash and non-cash itemized contributions for adjusted gross incomes of $1 million or more, plus half of contributions in the $500K-$1 million group; that year the bracket started at $540,000 for single filers and $648,000 for married filers, so some but not all of the giving in that income group would be in the top rate bracket. That’s about half of the Giving USA estimate for total individual giving that year of $356 billion.

If we are willing to assume that a 3% change in tax incentives causes a 3% decrease in half of individual giving, then it follows that we would expect this policy to cause a 1.5% decrease in total individual giving. (Math!) Taking the Giving USA 2024 estimate as a baseline, we should approximately expect this policy change to decrease giving by about $6 billion per year.

Is that a lot? It is not a prediction of the collapse of the US nonprofit sector, but it’s not nothing. $6 billion/year is equivalent to about three Mackenzie Scotts.Or putting this another way, all charitable giving by individuals in the US in 2014 equalled about 200 Mackenzie Scotts. Some charities will likely miss out on larger gifts than they would have received otherwise.

Giving to whom?

Of course, giving by Mackenzie Scott — and other high-income, large dollar-donors — is not uniformly distributed. Some causes and some organizations will be affected differently than others. Charities that primarily receive their gifts from many small-dollar non-itemizing donors may be better off, thanks to the expanded nonitemizers’ deduction; in this group will be churches and charities that do highly visible, mass fundraising campaigns. Other causes that prefer to develop big gifts from major donors will be disproportionately harmed; for example the arts, or many hospitals.Education too, although at the K-12 level the effect may be offset by a new 100% credit for scholarship fund donations.

And the charities themselves will adapt. The rising concentration of giving is not just a story of economic inequality among the donors, but one of fundraising strategies that have increasingly focused on landing a few large gifts at the expense of broadening the base of the donor pyramid. If the expanded nonitemizers’ deduction pushes charities to innovate in their recruitment of small-dollar donors, perhaps the 2025 tax reform will turn out to be just the nudge the sector needs for a stable, sustainable future.